About African-American Quilters:

The African-American Quilters’ Gathering (AAQG) of Harrisburg, PA brings together folks who enjoy creating beautiful works of art from bits of fabric. The group welcomes all quilting enthusiasts, regardless of race or gender. When folklorist Amy Skillman visited one of their monthly meetings, they talked with her about creativity, collaboration, and giving back to the community.

photo by Amy Skillman

About African-American Quilters

The first stitch

“A friend of mine coordinated a quilt show at Harrisburg Area Community College,” recalls founding member Carol Spigner. That was in 2007, during Black History Month. “She collected quilts from Philly and from local quilters... And, in the room with the quilts, there was such a buzz and such enthusiasm...”

Two years later, the pieces finally started to come together. “We asked people to bring their quilts, and anybody they knew who quilted,” recalls Carol. “And we went around the room and told the story of how we got to quilting. Then we asked people if they wanted to have a group, and so that was really the genesis... It’s been great fun.”

The African American Quilters Gathering of Harrisburg meets monthly and welcomes all quilting enthusiasts, regardless of race or gender. AAQG creates a space to enjoy creativity, to learn and share, to make mistakes and support one another, and to give back to the community.

Carol Spigner, who now lives in New Mexico, still joins each month via Zoom if she is available. For this meeting, there were three women joining via Zoom and nine women in person.

photo by Amy Skillman

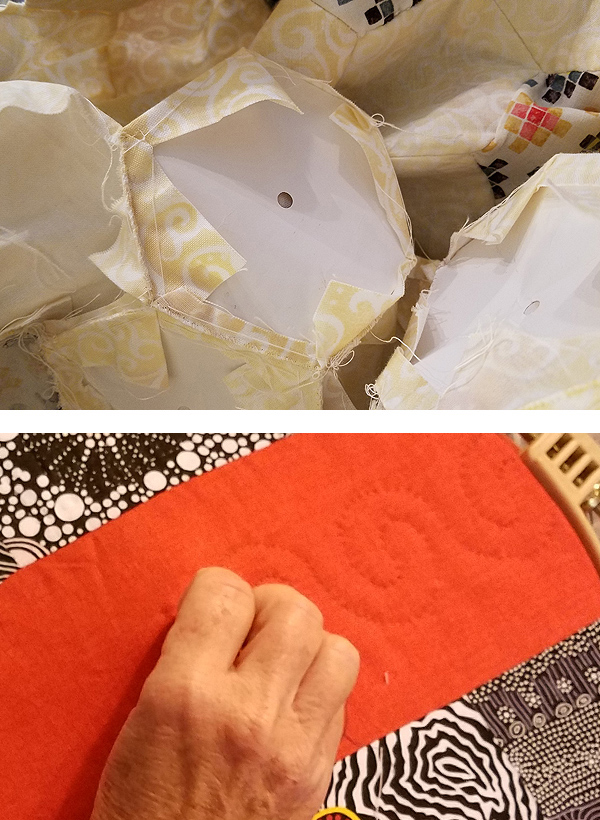

What makes a quilt

A quilt is composed of three layers: the top (with the pieced design), the filling (cotton or Dacron batting, flannel sheets, or an old blanket), and the back (usually a simpler design that complements the top).

Quilting is the process of stitching through all three layers, to hold the quilt together through wear and washing. That can be done by hand or with a sewing machine: either a regular or long-arm machine. It can be quite elaborate, with detailed floral or geometric patterns. Or, it might be quite simple and utilitarian: "tied" quilts have one big stitch every few inches.

photos by Amy Skillman

Every woman has their own aesthetic

Each gathering begins with a “show and tell,” giving members the opportunity to share what they have been creating and get input on design dilemmas. The quilts range from single‑panel baby quilts to full-sized bed coverings.

Carol says, “Every woman in this room has their own aesthetic, in terms of color, in terms of the way they like to work. As we work together, we can often look at a quilt and know who made it because their style is so distinctive.”

photos by Amy Skillman

photo by Amy Skillman

Carol says, “I’m just learning as I go. When I was growing up, I made garments, so I had that kind of foundation. But I find quilting much more creative. ... Even if people use patterns, their choices come from inside.”

“The more you do it, the better you get and there’s so many different ways to go. Every choice you make takes you down a different path.”

photo by Amy Skillman

Carol and others among the Harrisburg quilters agree. Quilters draw on their heritage as well as the full range of personal experiences in their lives.

photo by Amy Skillman

Patterns are everywhere

Liz Carter, who used to work in a fabric store, sees quilt patterns in everything. She recalls being inspired by a brick wall in a TV show she was watching. “I immediately jumped up, got a piece of paper and pencil, and drew it out. It’s a nice pattern!”

Marie Fourney has had the same experience with clothing: the fabric of someone’s dress might suggest a pattern. “You begin to see things differently,” agrees Liz, saying she’s not very creative about making her own patterns, “but once I see something, I think, that would be a nice pattern.”

The work of a lifetime

Narda LeCadre is another founding member of the African American Quilters Gathering of Harrisburg. A self-proclaimed night owl, she is often quilting at 2:00 or 3:00 in the morning. She has been quilting since 1974, and (like many quilters) made clothing long before she started quilting. After her mother passed away, she started dreaming about quilts, so she knew she had to make one.

photo courtesy of the artist

Narda still has that original quilt, and estimates there are over 300 of her quilts out in circulation. She also has about 120 tops at home waiting to be quilted. And since they do wear out, quilts often come back to her for repair and restoration. With 17 grandchildren and 6 great-grandchildren, she expects to be busy quilting for a long time.

Although most of her quilts are what she calls “utility quilts,” Narda is known for making quilts that have as much detail and design work on the back as they do on the front. She rarely has a plan when she starts a quilt. “I put two pieces together... and figure out a size for a block. Then I just fill it in, so it doesn’t necessarily make any kind of sense, but it works.”

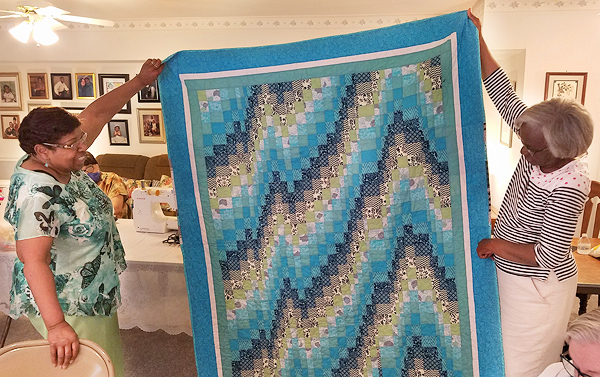

Creativity in collaboration

During the show-and-tell part of their day together, Marie Fourney shows a quilt she just finished. The question among the group is, whose quilt is it?

photo by Amy Skillman

The answer isn’t simple. Gloria Johnson made the top and gave it to Marie (“What a lovely gift to give,” Liz comments). Marie continues, “I created the back and then Laura did the quilting.”

When Liz Carter’s turn comes, she shows fabrics she has chosen and asks for advice on how to cut it so the pattern remains visible and foregrounded. When someone asks about batting, everyone choruses “That’s an Ann question!,” turning to their local expert on that topic.

This continues throughout their time together: excitedly sharing ideas, offering feedback, and supporting each other in their creativity.

By hand or by machine?

Ann Smyser is the go-to person for that final step of quilt-making, whether it’s to be done by hand or by machine. The time-consuming labor of hand quilting was traditionally shared (and still is!) by women gathered for a “quilting bee" with the quilt rolled onto a large frame. A home sewing machine is not well suited for the job, so Ann has invested in a long-arm quilting machine with a robotic arm. It can be programmed for any stitching pattern, opening up a whole range of creative possibilities.

“It’s a huge frame [much like that used for quilting bees], and you put your quilt in there and the machine ... moves along the width of the quilt to add the quilting to the area between the rails. Then you advance it, like you do with a traditional quilt frame, to quilt the next area.”

“The challenge,” Ann says, “is to pick a design that complements your quilt. For instance, this one [she points to one in her lap] is just solids and I wanted something to tie it together. I wanted the quilting to show a lot. And this one [points to another quilt] is really busy so I didn’t use such a bold design.”

photo by Amy Skillman

Piecing it together

The quilt pattern called “Grandmother’s Garden” is composed of many individual “flowers,” made of hexagonal petals that are cut individually and sewn together. Sharon England, who started quilting about 15 years ago, started one of these quilts last year.

While acknowledging that creating all those flowers is slow going, Sharon says, “I wanted to try something by hand. When you travel, it’s hard to bring a machine and everything, so this way all you need is your fabric.”

photo by Amy Skillman

Strengthening a community

Particularly among African American quilters, their art form has been a way to raise awareness and gather resources for social justice activities. In her essay “Kinship and Quilting: An Examination of an African-American Tradition,” Floris Barnett Cash traces the history of quilt making as both an economic and community effort.

Quilts were made and sold to help fund the Underground Railroad. Many women bought their freedom with money raised by the sale of their quilts. Annual fairs where quilts were sold or auctioned to raise funds have been traced back to anti-slavery initiatives in the early 1800s.

The Freedom Quilting Bee, launched in Alabama by Estelle Witherspoon during the Civil Rights Movement in 1966, rejuvenated quilting among African American women as both an economic activity and an initiative to register African American voters. That group continued their collective work until its last member passed away in 2012.

photo by Amy Skillman

More than a warm blanket

In this historical context, it is easy to see why community service is so important to these women. The majority of the quilts made in the group are made for charity. Recently, they have been making quilts for local children who are in the foster care system, providing homemade warmth for children who don’t always have warmth in their lives.

Pam Tulchinsky said “Sharon brought that group to our attention. Anyone who is able, participates. Ann did 22 quilts last year!” When Amy comments that this is a “hard act to follow,” Liz responds, “Well, we don’t try.” Sharon jumps in to say, “That’s what’s so great about this group. They are so nonjudgmental. They encourage everything. No such thing as [competition]. That’s why it’s so lovely to be here. I feel honored to be part of this group.”

Though the group’s members feel no sense of competition among themselves, they do enjoy a bit of friendly rivalry with other creator groups. In regard to Ann’s 22 quilts, one of the quilters said, “We are going to outdo the knitters and crocheters this year!” said one of the quilters.

photo by Amy Skillman

What you do with what you’ve got

Cherry Lewis brings out one of her quilts that is going to the foster care center. This is a Jelly Roll pattern: a set of 44 strips in complementary colors that are pre‑cut to 2½ inches wide.

Everyone raves about this quilt, with its hand quilting and rich shades of brown. The strips of fabric used to make it were unremarkable in themselves — the beauty came from how Cherry sewed them together.

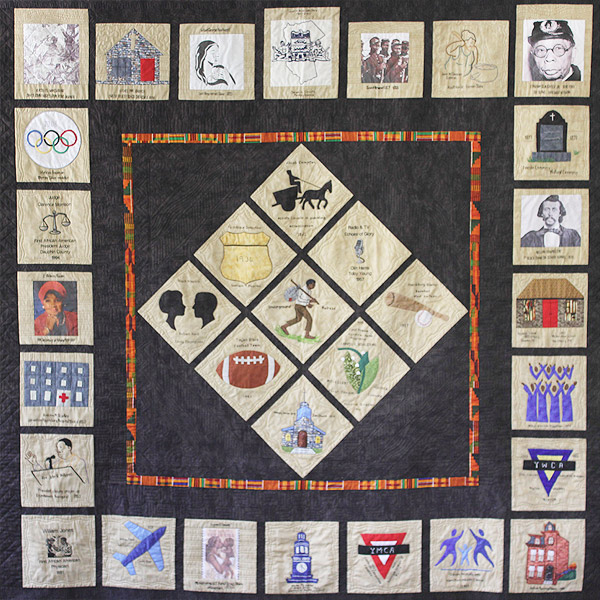

Quilts as a cultural record

In 2015, the African American Quilters Gathering of Harrisburg created a large quilt illustrating African American history in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania as part of Dauphin County’s 230th Anniversary. The quilt was unveiled at the Civil War Museum and is now housed with Dauphin County until they can make a hanging frame for it. Eventually it will go on display at the County Courthouse. For now, the quilt travels throughout the county and wherever it goes, the group is invited to be there.

photo courtesy of Carol Spigner

Each of the quilt’s large pictorial squares focuses on a person or historical event. This is a “story quilt,” similar in style to the Bible quilts made by African American folk artist Harriet Powers in the late 1800s.

Quilt scholar Patricia Ferrero, in her book Hearts and Hands, says that quilting bees functioned "as invaluable agents of cultural cohesion and group identity" for women. Barnett Cash agrees, saying that such community networks “formed the foundation for a new African-American culture” in the years following the Civil War.

“The basis of family structure and cooperation was an extended family of kinship ties, blood relations and non-kin as well. Female networks promoted self-reliance and self-help. They sustained hope and provided survival strategies. . . . Black women carried these concepts of mutual assistance with them from bondage to freedom.”

photo by Amy Skillman

“I’m inspired because these ladies are phenomenal. Their willingness to share what they know is really heartwarming for me. It’s almost like I’ve known them half of my life.”

See More, Learn More

The group meets monthly on the 4th Saturday of the month, in various locations, and all are welcome. For more information or to attend a meeting, contact Liz Carter at mizanna (at) verizon.net.

Footnotes:

1. Cash, Floris Barnett. “Kinship and Quilting: An Examination of an African-American Tradition,” The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 80, No. 1 (Winter, 1995), pp. 30-41.

2. Pat Ferrero, Elaine Hedges, and Julie Silber, Hearts and Hands: The Influence of Women and Quilts on American Society (San Francisco, 1987), p.48.

Brand icons for Facebook, YouTube, Instagram and other social media platforms are the trademark of their respective owners. No endorsement is implied.