About Julie Smith:

SFMS sadly shares the news that Julie Smith passed away on February 4th, 2024, at her home in Lebanon, PA. She is survived by her loving husband of over 26 years, William P. Smith, as well as four siblings and their families.

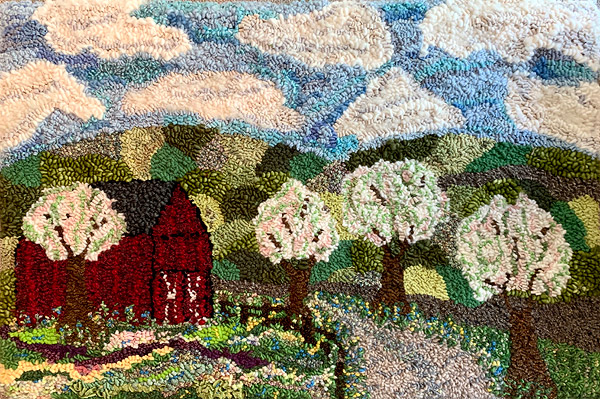

A talented designer and maker of hooked rugs and wall hangings, Julie was a member of the Woolwrights Hooking Guild in Lancaster, PA, and a member of the Association of Traditional Hooking Artists. She also enjoyed writing, reading, cooking and baking.

Memorial gifts can be made to the Lebanon Valley Council of the Arts, c/o Sharon Zook, 770 Cumberland St., Lebanon, PA 17042; or to the South Sixth Street Playground Association, c/o Sharon Zook, 525 S. Broad St., Lebanon, PA 17042.

portrait of Julie Smith by Amy Skillman

About Julie Smith

Julie Smith of Lebanon County, PA designs and makes hooked wool rugs and wall hangings. Her unique, organic creations take this historic artistic tradition in a fresh new direction. In May 2021, she spoke with folklorist Amy Skillman about what inspires her to create.

Women’s art

Women’s art, like women’s work, often falls through the cracks of cultural study: it’s not fully appreciated for the artistry it is. Warm quilts, delicious meals, well-made clothing and cozy floor coverings are traditional arts that women have practiced, mastered, shared, and passed on for countless generations.

The lovely and useful things that our grandmothers and great-aunts created are “tangible artifacts which can be read as cultural texts” — a record of the beliefs, practices and aesthetics of a time — say Art & Design scholars Laura McLauchlan and Joan Young in their article Out from Underfoot: Nova Scotian Hooked Rugs.1. They go on to say, “Because it does not belong to a Tradition of Past Masters, rug-hooking can be [understood] as part of an alternate tradition of cultural expression.”

The decorative hooked rug communicates through color and design what diaries and newspapers communicate through words.

Photo courtesy of the artist

Rug hooker Julie Smith describes that alternative expression as “a way for women who were so inclined, to be creative.” She goes on, “I do believe that it is harder for women to define themselves as something outside of motherhood and the home; harder to say, ‘I’m an artist’ than it is for a man who has a long lineage of great artists to follow.”

As an amateur historian of hooked rugs, Julie loves the duality of this traditional art. “Although it was useful, it was also decorative, which is amazing to me. They were doing it because they wanted warmth on the floor; they would make hearth rugs. And the hearth, of course, during the summer months is bare. So to make the hearth pretty, they would do rugs... I love that it was something that originated with women to release their creativity and to make the home comfortable.”

photo by Amy Skillman

Maritime origins

In their book American Hooked and Sewn Rugs: Folk Art Underfoot,2 Joel and Kate Kopp attribute rug-hooking’s rise in popularity to the introduction of jute burlap cloth in the early nineteenth century. Potatoes, coffee, grain, and many other products were shipped in “gunny sacks” made of this coarse, strong, inexpensive fabric. Burlap’s loose weave was easy to pull wool loops through, and empty gunny sacks were readily available. It’s easy to imagine housewives admiring their neighbors’ pretty handmade rugs and sharing their ideas with one another.

The Kopps note that one of the earliest dated hooked rugs was made by Abigail Smith of New Maryland, Nova Scotia in 1860. The Kopps link the first rugs in North America to coastal communities — to fishermen and their wives — and note a similarity between hooks used for net-mending and those used for making rugs.

It’s up for debate whether the making of hooked rugs actually originated in the Canadian Maritimes or in Northern Europe; England and Scandinavia are both contenders. But the tradition has a clear history in the Eastern coastal communities of North America since the mid-nineteenth century, and it spread widely on both continents.

Hooks and loops

Hooked rugs are made by using a hook to pull loops of colored wool (yarn or fabric strips) through a sturdy but loosely woven backing material. While early rug-hookers used burlap, Julie uses a linen backing material that has a tighter weave. Not every gap in the weave gets a loop pulled through it. Every second or third gap is more typical; it depends on the rug’s pattern and the width of the wool.

Julie draws the rug’s design directly on the backing material with markers, and stretches the backing taut on a frame to make the work easier. For larger pieces, the frame works like a scroll, with the completed part of the rug rolled up at the back and the uncompleted part rolled at the front.

The hook’s shaft is graduated so it gently enlarges the hole as it pushes through the backing material. Julie says it’s important to push the hook all the way down into the backing, so that the hole gets widened enough to pull the loop through. Julie only uses wool fabric strips or hand-dyed wool yarn for her creations.

photo by Amy Skillman

Organic creativity born of scarcity

Pennsylvania is home to a thriving rug hooking community, and Julie Smith is one of its enthusiastic proponents. “I come by my creativity pretty organically because both of my parents were very creative. My father was a furniture maker in addition to owning a gas station. So, he was an artist, but it wasn’t what he did for a living. And my mother was an avid sewer. She sewed all of our dresses when we were kids. Both of my grandmothers were quilters and knitters and crocheters; the tatted lace and everything. So I grew up amongst all of that.” She adds, with a chuckle, “You can’t escape from that unscathed.”

Like so many art forms practiced in the home, rug-hooking springs from a scarcity of materials and time. In between other household responsibilities, women recycled worn clothes and old blankets to create comfort, warmth, and beauty — using the stuff of the past in anticipation of the future. Julie’s early life affirms this. “My father had his own business but it wasn’t what I would call wildly successful, so money was not plentiful.”

Recognizing her creative energy, people bought her latch hook kits from the craft store. These were pre-stamped kits with all the materials needed to hook a small design using a special hook. “It would keep me away from my Mom’s sewing machine, which she appreciated, because I was always experimenting.” As a young adult, she dabbled in sewing, making pillows and purses, while pursuing a 15-year career as a floral designer and store manager. Then one day she saw an announcement for a class on rug hooking and thought it would be fun to reconnect with a childhood craft. “I took a chance and I loved it.”

Not a rule follower

photo by Amy Skillman

Even during her first rug-hooking class, Julie asked the instructor if she could embellish the basic pattern given to the participants. It was a single flower in a vase, with one color for the petals and one for the stem and leaves. Julie wanted to add shading — she observes wryly that she never was good at following rules.

The instructor encouraged Julie’s creativity, and not only showed her how to add shading, but also how to add dimension. The stamens in the center of the flower are made with a stitch called ‘proddy’ to make them stand up above the surrounding pile. The adjacent photo shows how well her first effort turned out: note the shading in the petals and the design on the vase.

photo by Amy Skillman

Inspiration from Nova Scotia

Julie works out of her home studio on 27 acres of woods outside Mt. Gretna. Large open windows bring in the light, and she is “filling it up with color.” Of the 15 or so rugs that hang on her walls, only two (Coastal Girls and Grey Barn) are the designs of another artist. All the other designs come from her own imagination.

The two designs that are not Julie’s come from Deanne Fitzpatrick, a rug hooker from Nova Scotia, Canada. When Julie was taking that first class, the instructor said Julie’s work reminded her of Deanne Fitzpatrick’s. Julie hadn’t heard of her, so the instructor brought in a magazine article about Fitzpatrick. Julie was immediately inspired. “She does a lot of fields, and her method is painting with wool.”

Fitzpatrick’s influence is apparent in some of Julie’s work where the fields and sky have a painterly feel — highlighting the medium (dyed wool) as much as the content. For instance, she might use swirls, puffs, leaves, curlicues, s-shapes and even horizontal or vertical stripes for the sky. “I go with how it moves me... It’s very abstract, but you can tell what they are. Almost like an Impressionist [painting].”

photo courtesy of the artist

Inspiration from nature

“I am very inspired by the outdoors, always have been. My dad was a Boy Scout leader. I wasn’t allowed to be in Boy Scouts at that point, but all my brothers were, so obviously that just naturally rubbed off. We’d go for nature walks; names of trees, names of birds, names of flowers and everything. So I have always been inspired by nature.” Julie is also a landscape photographer and often uses her photography to design a rug. “So everything that I do comes from nature; even the abstract pieces. Sometimes you don’t want to be so literal... ”

photo by Amy Skillman

”I like the ephemeral nature of what you see outside. Every day it changes.”

While her inspiration comes from the landscape around her, she is also inspired by art from around the world. Julie grew up along the Swatara Creek and her rug called Red Creek depicts what she recalls, with flowers along the banks and the river running through the middle. “I had been looking at a lot of aboriginal art at the time when I designed this piece, and I loved the flow of it and the slashes with the natural curves. But it was also very geometric, so I did some of that. Some of it I ripped out because I didn’t like the geometrics as much as I liked the organic. It has some proddy [the stitch that stands higher than the rest]... in the flower forms.”

On the other hand, she notes that her most recent work, Goose Moon Rising, is very “fantastical,” depicting a goose in flight above an enormous full moon rising out of a line of trees. This piece is inspired by photography and also by her experiences using Photoshop to create pictures. Goose Moon Rising is the second in a series called Migration.

photo courtesy of the artist

Julie admits to being fascinated with tree lines. They show up in so many of her pieces, perhaps because the rolling farmland of Pennsylvania’s Lebanon and Lancaster Counties affords so many views of tree lines across open fields.

“I have a background in quilting from both of my grandmothers... So when I drive down Butler Road to my home, and I see the mountain, it looks like a patchwork of green to me. So I thought, I want to do a patchwork of green for the mountains.”

photo courtesy of the artist

Getting it right

Like any art form, the result isn’t always what Julie had in mind. “With rug hooking, you can plan out everything, and you can buy all your fabric and everything, and when you’re doing it, you put in something and it just doesn’t feel right. It just doesn’t work. So, I love that you can rip stuff out and just redo it.” As an example, she had a hand-dyed yarn called Canada Goose that she really wanted to use in Goose Moon Rising, but struggled to find the right material to complement it. She made the outline in wool strips and filled it in with the yarn, pulling it out and redoing it several times, trying different tones of wool fabric to blend with the yarn. She was determined to achieve the effect she had in her imagination.

photo by Amy Skillman

“When you spend so much time designing it and making it, I just have a hard time wanting to put it on the floor. I’d rather hang it on the wall and look at it.”

From the parlor floor to the gallery wall

In his article Hooked Rugs in Newfoundland: The Representation of Social Structure in Design, folklorist Gerald Pocius says, “...in the hooked-rug tradition, a woman had two major choices in the selection of a design. She could adopt the community’s norms and utilize a geometric pattern that had been widely used over time. Or, in contrast, a woman could elect to be innovative, and introduce a design outside the community’s repertoire, either from commercial sources, or more commonly her own composition.” 3

Pocius notes that the rug with the community-based design often ended up in the kitchen, the communal space, whereas the rug with the innovative design was placed in the parlor where the family hosted special guests. Thus, the woman’s individual creativity was given a gallery of sorts. Julie clearly fits this latter group of rug hookers: able to imagine an idea, sketch it out in a notebook, and then adapt it to the size she wants to create.

photo courtesy of the artist

As Pocius notes, “The highest degree of innovation with design sources involves the mental assemblage of ordinary objects into an image to be used specifically for a rug, and not merely an attempt to copy a concrete holistic model.”

Julie says, “I would do a piece for the floor, if I had need for it. But it is a different aesthetic. I wouldn’t put this [pointing to a piece with a yellow background] on the floor. It doesn’t make sense.” Instead, she would design something that is meant to be seen from above.

photo by Amy Skillman

“It is fascinating to me that something that started out to be put on the floor, using simple household things, to reutilize worn out items, and was so utilitarian that you didn’t even think about it... you literally wiped your feet on it... [It is fascinating to me] that this is now elevated to the point that it is available in a gallery — an art. ...And yet, people are reluctant to call it art, but it really is. It is often that way with women’s art.”

“You can call me crafty or you can call me an artist. I call myself an artist because I know that is what I am.”

photo courtesy of the artist

What’s next for Julie?

Julie is considering tackling people as a subject. She has done some sketches and is hoping to create a piece that will honor a friend she has lost. She also recently found an old quilt frame at an antiques market and hopes to convert it into a hooking frame so she can make bigger rugs. She is interested in teaching this rewarding art form to others.

And, in the coming year, Julie plans to travel to Nova Scotia to research the Canadian Maritime rug hooking tradition and finally meet Deanne Fitzpatrick — to meet, in person, the woman who has inspired and encouraged much of her design work.

Rug-hooking resources

- Julie Smith doesn’t have a website yet, but she can be contacted at julesasmith.js@gmail.com

- Association of Traditional Hooking Artists (ATHA) — an international fellowship of artists that fosters individuality and diversity in rug hooking.

- Woolwrights — a Pennsylvania chapter of ATHA, based in Lancaster County

- National Guild of Pearl K. McGown Hookrafters - McGownGuild.com — an organization named in honor of a the person who began promoting rug hooking as an art in the 1930s. She formalized and promoted the concept of shading in designs.

- Deanne Fitzpatrick - HookingRugs.com — a rug hooking artist from Nova Scotia whom Julie especially admires.

Goose Moon Rising, created by Julie Smith

Footnote:

1. McLauchan, Laura and Joan Young. (1995) “Out from Underfoot: Nova Scotian Hooked Rugs.” Atlantis, Vol. 20, No 1, pp 95-100.

2. Kopp, Joel and Kate Kopp. (1995) American Hooked and Sewn Rugs: Folk Art Underfoot, University of New Mexico Press.

3. Pocius, Gerald L. (1979) “Hooked Rugs in Newfoundland: The Representation of Social Structure in Design.” The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 92, No. 365. pp. 273-284.

Brand icons for Facebook, YouTube, Instagram and other social media platforms are the trademark of their respective owners. No endorsement is implied.